Robots are some way off from taking over from humans, but collaborations between the two 'workforces' are becoming ever more productive

Robotic manufacturing is set to revolutionise even industries like the floral and associated packaging market (Credit: jul_G/Shutterstock.com)

While we are some time away from robots taking over the world, it is true they are being more widely adapted as technology improves. Two major areas over the past few years have been in automation and collaborative robotics, where robots work directly with humans to achieve excellence. Packaging Today presents an article by the contributing editor for Robotics Industries Association, Tanya Anandan, which explores collaborative robotics in action with some of the organisation’s members.

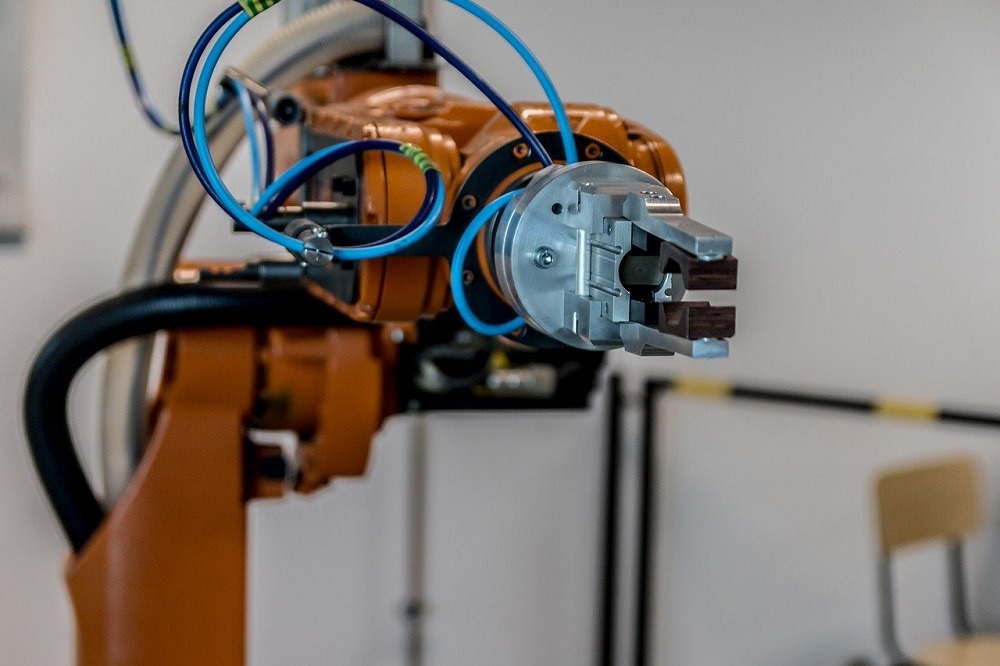

Robots come in many shapes and sizes, are function-led, and not easy to categorise. They might pick, place, lift, move or otherwise assemble pieces or products; they can solder and do precise engineering tasks, or lift tonnes of materials and move them onto trucks, and they can work alone or in sequence – and everything in between. What robots can also do is provide humans with a point of interaction that makes their lives easier and produces faster, higher-quality products in conjunction with human operators, hence the collaborative name attached to them – cobots. Labour issues? No problem: a well-placed cobot can take the strain and stress out of a situation. Ultimately they can elevate the jobs and work of humans by taking on the tasks that are limited, repetitive or not possible for humans to do at high speed or efficiency.

Take iClick, a West Coast manufacturer of promotional products, which was encountering a labour shortage that directly affected its manufacturing flow. The company, which makes grips for mobile phones, was seeing vast volume increases in demand but was unable to acquire the human personnel to keep up. Workers had to manually put grips onto promotional cars and feed them individually into a bagging machine – an extremely labour-intensive process. Even four employees working together could not get close to the required output, and staff turnover in these positions was incredibly high.

House of Design, a robot integrator company, solved iClick’s problems by developing the FlexBagger system. The robotic kitting and bagging system consists of two ABB YuMi dual-arm collaborative robots, and, with its seven-axis arms working in unison, each robot attaches the grips to the promotional card and after drops them into an automated bagging machine.

The robots occupy the same space that they deposit the bagged items, meaning they have to be minutely coordinated to ensure there are no collisions. House of Design used ABB’s Robot Studio to make sure each workstation was fully programmed to allow for smooth movement in arms, without cross over or crashes.

According to Chad Svedin, project manager for House of Design, one of the crucial steps was in coordinating the bagging process. “Human workers can’t bag the products fast enough,” he says. “Two dual-arm robots can perform the work of four people, and keep the automated bagger fully stocked.” Ultimately, this first use of collaborative robotics was so successful in 2018 that they ordered another system a year later.

YuMi and the robots designed for human safety

Like other power and force-limiting cobots, YuMi has special characteristics to help it work in close proximity or directly with its human co-workers. It was important to iClick to have a collaborative robot, so its workforce could easily enter the robots’ operating space to remove defective items or replenish products when necessary. The dark grey areas on YuMi’s arms are padded for safety in the event of contact.

“If someone juts their hand into the working system, it bumps into them and freezes in its spot,” explains Svedin. “A minor bump will stop it from moving.”

House of Design trained iClick personnel on safety, and how to run and program the robots. “They loved that the robots looked very humanlike, and that they could approach it,” Svedin says. “It wasn’t this thing in a box away from them. They saw it as a part of their crew.”

While manufacturing might seem like a reasonable and potentially obvious location for robots to play a key role, they are certainly not the only industry with labour shortages that could be reduced and resolved through application of the right cobot. A slightly less obvious industry with an impending labour crisis, which has been looking to automation for support recently, is the floral industry.

Cobot’s kiss from a rose

At the Automate show last year, visitors saw a cobot arranging bouquets of roses. FloraBot is the brainchild of founder and CEO Alex Frost, a second-generation florist who grew up in his parents’ retail flower business. For the past dozen years, Frost’s Fort Lauderdale, Florida-based software company, QuickFlora, has been providing cloud-based ERP systems for floral retailers across North America.

“We work with a lot of retailers in the US and Canada, helping them manage their software technology front-end and back-end systems,” Frost says. “We have a front-row seat to some of their challenges. Over the last five to 10 years, there have been fewer and fewer people going into the flower business, so it’s hard to find qualified floral designers to work in flower shops.”

He said that issue is compounded by an increase in minimum wage rates in places such as California, a development equal to a real labour shortage in the floral industry. It’s an environment he thinks is ripe for collaborative robots.

“We see them flipping hamburgers, making pancakes and serving coffee,” he notes. “We decided last year, let’s bring one of these machines in here and see what it can actually do. Can we program it to make flower arrangements? Can we create a turnkey cell for end users?

“If you think of Kroger [a US national supermarket retailer], they have 4,000 stores across the country, marketed under different supermarket brands. Each store needs about 10 to 30 arrangements every day,” Frost continues. “Those are all made by hand right now – usually, you have 50 to 100 people in a cooler. The process is very labour-intensive and you can’t scale it. When Valentine’s Day or Mother’s Day comes around and volume increases five or 10 times, you can’t just hire five or 10 times the people that fast when you don’t have space. There’s a labour shortage issue, a labour cost issue and a scalability issue.”

The emerging market that Frost spies is not limited to North America. In fact, Western Europe is behind a large number of incoming business opportunities as labour costs are higher, and the market has shown itself more adaptive of automation technologies. Frost sees a new niche for precision agriculture where cobots are providing farming support.

“We sort of fit into that category because we’re dealing with product that is very sensitive, not heavy, that requires specialised grippers, force control and vision systems to actually make it work,” Frost says. “There are a lot of similarities between our technology and that technology, in terms of trying to handle delicate flower stems of all shapes and sizes, and then pick and place them into specific xyz coordinates, with reasonable cycle time and low defect rate.”

He started with a Universal Robots collaborative robot, because of their relative ease of use and ease of programming. They have a built-in ecosystem of compatible hardware makers and apps. They’re also easily portable. The current FloraBot system uses a UR5 cobot with a Robotiq Hand-E gripper. Previous testing was conducted with grippers from companies Ubiros and Soft Robotics.

Frost said the gripper system has been a big part of the learning process. “What we realised is that nothing worked off the shelf. Absolutely nothing. We had to come up with our own proprietary fingers. Now we’re working on our own proprietary servo-electric gripper. It will give our end users more flexibility.”

Commerce is our goal for the technology

The resultant systems are still pending a patent, but first units started shipping in 2020. According to Frost, the latest cobots can assemble American Institute of Floral Designers-quality floral arrangements at 100–200 units per hour, 24/7, and with a return of investment in less than a year. Right now, they plan to sell the system, but eventually, he expects to move to a robot-as-a-service model. This will remove the requirement of buying a more expensive capex model.

The current robot is best with small bouquets that are about a foot long. Larger arrangements, such as long-stemmed flowers, need a different grip, an innovation that FloraBot will have to create proprietary products of its own to manage. Frost’s future vision sees a bespoke system shipping on 48×48in pallets, a single cell performing tasks in the assembly line – each robot doing one part of the final arrangement in line.

“Right now, we see that the machines are capable of doing 75% of what humans do in the floral business, whether it’s a typical flower shop or the mass market,” Frost said. “That’s really the sweet spot for this technology, the mass market, because they crank out high volumes [2,000–3,000 bouquets] of the same type of arrangements on a daily basis. There will always be a market for people that want something custom. But the reality is most retail florists make the same arrangements week in and week out.”

FloraBot has been approached by companies that put flower arrangements in boxes and ship them around the world. There are a lot of new, innovative players in the flower business. Frost says most of the new upstarts are the most receptive to automation.

Frost continues: “We’ve had requests to do Hawaiian flower leis, which is a very labour-intensive process. Others want us to make different animals covered with roses, which is popular in many countries. That’s also very labour-intensive because you have to cut out a foam model of a little French poodle, and then put 600 roses on it. That usually takes four to eight hours. There are definitely cases where machines will take over in terms of production capability.

Frost wants consumers to be unable to differentiate between what was created by one of the robots, and not care, keeping the quality high and still delivering value for them. He sees a human-less flower arranging future: “it just doesn’t make economic sense anymore”.

The full article is available at www.robotics.org.

This article originally appeared in the Spring/Summer 2020 edition of Packaging Today. The full issue can be viewed here.