With the rise of microplastics in the world's environment, Thomas Parker looks at what they are, how they are produced and what can be done to curb the effects

(Credit: Wikimedia/www.raceforwater.org/Peter Charaff)

As part of its 2017 Clean Seas campaign, the United Nations (UN) reported there were 51 trillion microplastic pieces in the world’s oceans – 500-times more than there are stars in the Milky Way galaxy.

But it’s not just under sea where microplastics can be found.

Where are microplastics found?

Between November 2017 and March 2018, a team of researchers from France and Scotland regularly collected samples in a remote part of the French side of the Pyrenees Mountains.

The researchers’ report, published in April 2019 in science publication Nature Geoscience, concluded that every square metre of ground sampled accumulated around 365 pieces of microplastic per day.

According to research by the Medical University of Vienna, plastics can even end up in consumers’ food.

The researchers took samples of faeces from five women and three men from eight different countries in Europe and Asia.

They also asked participants of the study to keep a nutrition diary for one week.

Bettina Liebmann, from Austria’s Federal Environment Agency, analysed the samples and discovered microplastics in them.

She said: “In our laboratory, we were able to detect nine different types of plastics ranging in size from 50 to 500 micrometres.

“Due to the small number of volunteers, we are unable to establish a reliable connection between nutritional behaviour and exposure to microplastics.”

But what are microplastics, how did they first come into existence, and what can be done to curb the threat they pose?

What are microplastics?

The term microplastic is used to describe plastic debris smaller than five millimetres in diameter, and can be used to describe particles as small as 10 nanometres.

According to research body The Joint Group of Experts on Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection (GESAMP), most microplastics are produced from litter that degrades on beaches.

The process starts when larger plastic items are hit with UV irradiation, before being submerged in the sea, which causes fragmentation to occur extremely slowly.

The term mircoplastic was first coined in a 2004 study named Lost at Sea: Where Is All the Plastic?

This study was co-authored by researchers from the University of Plymouth, University of Southampton and Sir Alister Hardy Foundation for Ocean Science.

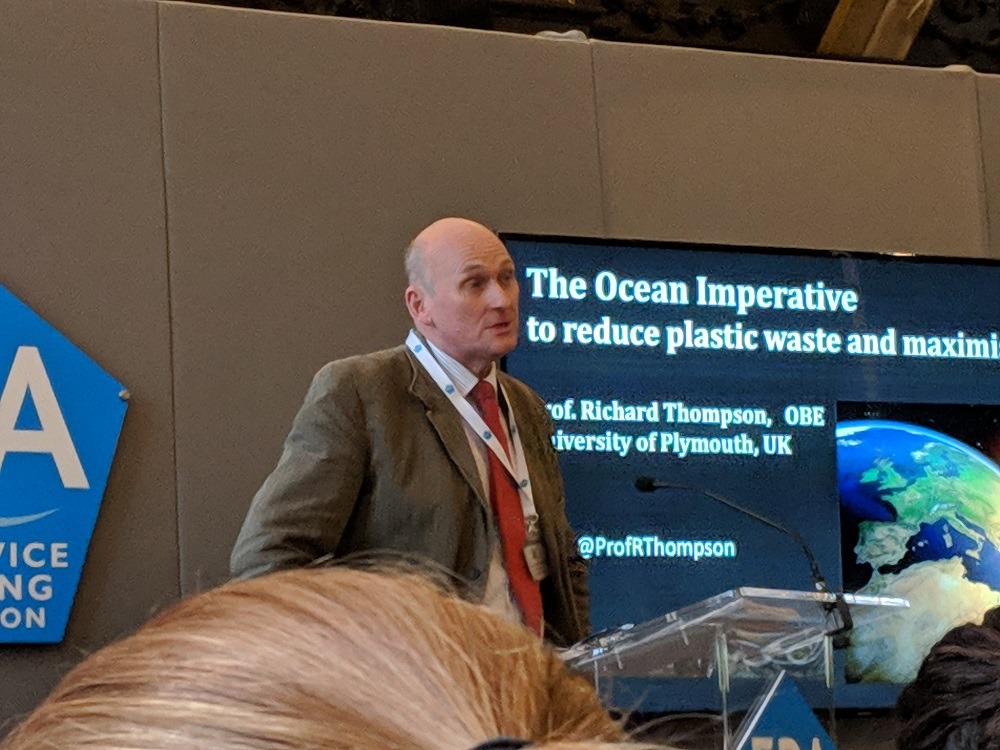

Speaking at the Foodservice Packaging Association’s Environment Seminar in 2019, the study’s co-author Professor Richard Thompson, head of the international marine litter research unit at the University of Plymouth, said: “When we first coined the term mircoplastic, there was only one paper on it.

“In 2018, there were 300 scientific papers on microplastics alone.”

What are nanoplastics?

It’s now believed by some scientists that plastics have degraded so far that some have reached sizes measurable by nanoscales – turning them into nanoplastics.

Researchers at the Sweden-based Lund University conducted a study to find out if this was possible in 2018.

To do this, they subjected products like coffee cup lids to mechanical degradation, to mimic what happens when plastic ends up in the ocean and see if the material reached the size of a nanoplastic.

Tommy Cedervall, a chemistry researcher on the project, said: “We have been able to show the mechanical effect on the plastic causes the disintegration of plastic down to nano-sized plastic fragments.

“It’s important to begin mapping what happens to disintegrated plastic in nature.”

What can be done to curb the effects of microplastics and nanoplastics?

The British House of Commons’ Environmental Audit Committee’s report into microplastics in 2016 and 2017 highlighted one of its biggest issues – its size.

Because of this factor, it would be easy for the material to be ingested by marine life, though it is difficult to make predictions about the risks of ingesting microplastics.

The UN’s Sustainable Development Programme outlined a few ways to make a difference in 2016.

It said, by 2030, the proportion of untreated wastewater should be halved to reduce the adverse environmental impact of cities and substantially reduce waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling and reuse.

In 2017, the UN’s Environmental Programme urged the global population to “stem the growing tide of maritime litter” through the reduction of single-use plastics at the individual level, by taking measures like reusing shopping bags and water bottles.

At the time the programme was announced, Peter Thomson, former president of the UN General Assembly, said: “The ocean is the lifeblood of our planet, yet we are poisoning it with millions of tonnes of plastic every year.

“Be it a tax on plastic bags or a ban on microbeads in cosmetics, each country can do their bit to maintain the integrity of life in the ocean.”

Since this announcement, progress has been made.

In October 2018, circular economy charity the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, in collaboration with UN Environment, set up the New Plastics Economy Global Commitment, which brought together over 250 organisations and governments committed to reducing the amount of plastic in the ocean.

In a report published in early March, major companies including The Coca-Cola Company, Nestlé and Mars Incorporated made a commitment to increase the amount of recycled plastic in all their packaging by 25% by 2025 – compared to the current global average of just 2%.

New Plastics Economy campaign leader Sander Defruyt said: “The targets and action plans set out in this report are a significant step forward compared with the pace of change in past decades.

“However, they are still far from truly matching the scale of the problem, particularly when it comes to the elimination of unnecessary items and innovations towards reuse models.

“Ambition levels must continue to rise to make real strides in addressing global plastic pollution by 2025, and moving from commitment to action is crucial.

“Major investments, innovations, and transformation programmes need to start now.”