Flexible packaging accounts for more than half the packaging mix across all categories (except beverages), and is widely recognised and lauded for its lightweight, excellent barrier properties and ability to preserve and protect products. Guido Aufdemkamp, executive director of Flexible Packaging Europe, relays the current state of the sector, and its objectives and goals for the imminent and medium-term future.

While Europe might lead the way for a lot of the circular economy discussions and legislation, it is important to remember that each global region is different and has its own priorities, with a number of fundamental differences in how we handle waste. Overall, Europe tends to be at the advance of circular economy discussions, and, even with subtle or major differences in waste management, tends to lead the way.

Flexible packs more than half of the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG), with the exception of beverages – for the latter, while flexible still appears as pouches to hold items like kids’ juices and wine, it is dwarfed in usage when compared with PET bottles or other rigid containers.

Flexible packaging is everywhere in the packaging mix, and one of packaging’s main challenges, at least from the consumer side, is addressing the perception that flexible is bad for the environment.

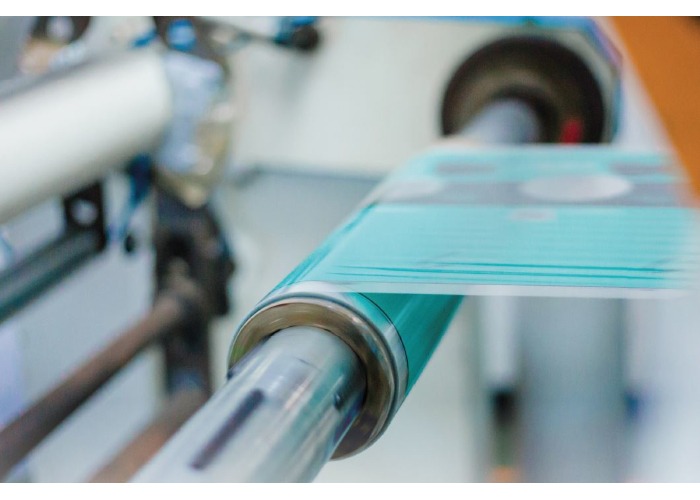

The general concept of flexible is to use the least amount of material necessary: if the product cannot perform, then another layer can be added, but at the absolute minimum needed to accomplish the quality and function desired. Therefore, flexible packaging is always tailor-made to the product it protects, whether it’s fresh or a retort, if it requires an ambient environment or a more chilled one. For this reason, there can be multiple materials in the same package; sometimes more paper, sometimes more plastic, sometimes more aluminium. The manufacture is specific to the product being protected. This is why flexible has become such an exciting sector to work in.

As a by-product, these engineered structures provide excellent barriers and shelf life enhancement. Although consumers are looking for more sustainable solutions, flexible packaging cannot simply be taken away because that is what provides the barrier and performance. The product would be poorer, and the consumer would be less likely to buy it. Markets have shown that people aren’t willing or able to give up the convenience and function of flexible packaging. This is despite a wide desire to reduce the amount of waste that modern societies produce.

Organic waste

While consumers might focus on packaging waste, a bigger issue is food waste. Many think that food waste is organic and easy to return to the planet, meaning there is no problem. But the resources splurged on creating, harvesting and shipping produce to a point of purchase and use are enormous. If food is not eaten it is a waste of resources, and if it goes off before even being sold, that is an even bigger waste as there is no return on investment – just massive costs.

For those in flexible packaging, however, the focus is very much on the attainment of a circular economy, which would provide the maximum use of resources for the minimum impact, socially, financially and environmentally. One difficulty is that flexible packaging is not recycled everywhere. Even in Europe, flexible packaging is not part of the packaging collection system. This is something that must change.

Recycling rates can even differ inside a country itself, because of different collections and infrastructure. Throughout Europe, community by community, region by region, there is a waste management system that is super fragmented. This is another challenge.

Another is that though the system is heavily fragmented, brand owners still pay extended producer responsibility fees. It is a burden that they pay the expense for a system, but the system does not completely cover or resolve the issues.

Until recently, the recycling rate targets could always be met without taking up the challenge of collecting and recycling flexible packaging. Because it’s lightweight, and the recycling targets are weight-based, it takes a massive amount of flexible packaging to weigh much. This was one of the reasons behind Flexible Packaging Europe’s CEFLEX initiative, which focused on the journey of flexible packaging to a circular economy.

With the incoming packaging commitments that all packaging must be recyclable, and brand commitments and legislative focus on making this a reality by 2030, the focus turns on how industry can make flexible circular so it fits into this ideal.

Step one

Overall, there are two main ways to make flexible packaging circular. Either adapt the material composition to the existing waste management infrastructure, or upgrade the waste management infrastructure – for example, add new technologies. Flexible Packaging Europe believes that, for maximum effect, it is best to incorporate both.

As there are so many different structures to flexible packaging, the recycling processes differ. There is no simple way to do all recycling, and even if a more efficient way is developed, there still has to be a way to scale up the new technologies and bring them on board to have the maximum effect. This also applies to mechanical and chemical recycling. Under current legislation, output of mechanical recycling cannot be used for food contact-grade materials. This is another of those layers of complication in the waste management stream. Though mechanical recycling is efficient, legislation and food safety concerns mean there is no room for even a window of doubt that the process could allow any contamination or loss of barrier. In fact, every plant has to be individually approved in the recycling process by the EU; a successful plant can’t simply be copied and expected to be rubber stamped.

Why not use a refill model? The pouch is not refillable and not reusable so a food contact certification would not work – but the material they are made from is. That is why the focus is on recycling as that is where the biggest impact can be made. Flexible packaging is so lightweight that very little waste is generated. And even that almost non-volume is being put into a circular economy.

Refill seems sensible from the outside, but if you consider the logistics of transporting an empty pouch, cleaning it, then shipping it to the refilling line, then more shipping to return to the customer, it adds a lot of layers in which an empty product is being shipped.

A further challenge with amending the material structure is that many things that were not recyclable five or ten years ago are today, and new plants being constructed have far more capable technology than previous ones did. However, it is not uniform or widespread, which adds to the complexities of local level waste management. Consumers don’t know that there is a chance their waste gets managed more efficiently or not as they have no way to influence this, and so packaging, even if it could be recycled, is not because it is in the wrong stream or location. This is replicated across thousands of local areas and nationally.

Might it be better to substitute the material composition for another that may be more sustainable or less wasteful, passing on quality control and scale, and focusing on recycling technology potential and capacity?

In the UK, there is already the Enval technology operating, which can perfectly recycle multimaterial laminates. Other technologies in the field of chemical recycling are also being installed and further developed. The technology is here, incoming and commercially viable. That’s what we consider the most important thing; it works and it also makes money. For example, Enval is working with Sonoco and Kraft in the US to build plants that fully recycle materials, and close the loop on production waste. The US has historically been less concerned by the environment, and so when such major companies are looking at this technology and using it, it is proof they can justify an economic reason as well as telling consumers it is for environmental ones too.

Big moves

Ultimately, it is probably better to reuse the material than the package. Flexible Packaging Europe conducted a study that found if all flexible packaging could be recycled, more than 21 million tonnes of material would be saved. To highlight just how large this is, that represents about one third to 40% of the entire material usage for all packaging. In CO2 terms, this is almost half a percentage of the entire European emissions. That might seem small, but that entire scope includes everything: transport, manufacture, travel. And that can be gained from something as simple as moving into flexibles.

We are not telling people to do this, it is just important to understand the impact that flexible packaging has on the waste stream when compared with other materials. Recycling is not the only way to make a difference; all options have to be considered.

To summarise where flexible packaging is and where it is going, the biggest legislative focus is on the revision of the European Commission’s Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive, including the essential requirements that all packaging will have to be recyclable by 2030. This does not mean in theory recyclable, or a percentage, but all packaging to be 100% recyclable. Legislation is also on its way to harmonise the calculation of recycling rates so they are more uniform within the EU. There is also the SUP guidance and the EU’s plastic levy, and how it will be implemented across member states. Meanwhile, because of Covid-19, there was a small peak in the use of flexible packaging in the first half of 2020, from March to June, and then a fall-off.

These focal points, in combination with Flexible Packaging Europe’s overall aim to make flexible packaging sit firmly in the circular economy, are the main focus for the organisation in the immediate future.